Now that you have a plan for your search it’s time to Look! But don’t just look – Look WELL!

It’s simply a matter of typing a name in a search box and hitting “Enter.”

Or a matter of making one quick phone call.

Or getting the right book in your hands and immediately turning to the right page.

Right??

Sorry to burst that bubble, but searching for answers is not always so easy. It DOES happen that way sometimes.

But I think one reason we call it RE-search is because many times, it will take some RE-thinking and some RE-searching of the same collections with new eyes.

By “look WELL” I mean that you will need to

- keep an open mind about search parameters

- take good notes of what you find (and don’t find) as you go (more on that in a future post!)

- and behave well to those you encounter as you search.

Search Parameters

Consider a wide variety of spellings for your ancestor’s names. Some online research collections will allow you to search using wildcards. Find out what wildcards are used on the website you are on and apply them as directed. In non-indexed and/or non-computer research, you may simply have to keep a running list of the spelling variations you’ve brainstormed and keep that handy as you search.

In addition to playing with name spellings, consider that person may have gone by their first name at one time and by their middle name at another time. A married woman may have reverted to her maiden surname.

And/or try only inputting one name at a time (i.e. search by first name only or by surname only, not the combination of First+Last).

I will share two examples from researching my German-American ancestors in US census records.

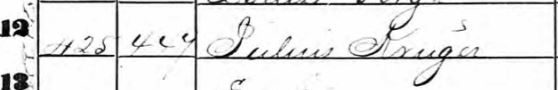

First, when looking for a man named Julius Kruger on the 1860 US Census, I was surprised not to be able to find a Julius in my expected locality. Instead, an indexer on Ancestry said there was a Pulius Kruger living there. I must admit, the enumerator’s flowery script does indeed make it difficult to distinguish a P from a J on this page, don’t you think?

In a second instance, I could make no headway at all in searching for Ferdinand Kraetzner in the 1870 US Census in the place where I’d found him on the 1860 US Census. The use of wildcards had not helped. For instance, searching for Ferdinand K* pulled up three men with surnames Kauss, Krueger, and Kukhohn, none of which were very close to Kraetzner.[1] And besides, those Ferdinand K’s had the wrong names listed for their wives and children.

I finally searched for Ferdinand without any surname at all and voila! Among the 45 results that pulled up was a Ferdinand Gratzeler, married to a woman by the correct name (Caroline) and so forth.[2] Clearly, Ancestry’s “sounds like” algorithms and my poor brainstorming had not gone so far as to think of Gratzeler as a substitute for Kraetzner. But again, I must admit that from the enumerator’s point of view, hearing a German immigrant say Kraetzner and writing down Gratzeler maybe wasn’t too shabby a job.

Also try widening the span of years included in your search. You may have convincing evidence that your ancestor was born in X year, but if you refine your search to the degree that ONLY that year will come up as a possibility, well, you may not find them.

Birth years are often mis-recorded, either intentionally or unintentionally. For instance, a male may have desired to be older so he could enlist in the military. Or a mother may have wanted to hide her son from a draft, so she changed his birth year to give the appearance that he was younger. Girls fudged ages to marry without parental consent, census enumerators were sometimes poor judges of age. All it takes is one little transcription error and ever after, your person who actually died in 1824 appears on record to have died in 1842. The list goes on and on.

Take-away: if at first you don’t succeed, try looking in another year.

Also consider casting a wider geographical net. If you have thoroughly searched the marriage books for one county for ten or twenty years before and after you expected to see your couple and come up with nothing, maybe it’s time to try the next county over. Or do a search for “Gretna Greens” in the region and search the books for that county.

Another method of tweaking my search that I frequently employ: search for a different family member first. Females before the 20th century can be particularly elusive. Perhaps try searching for a female ancestor’s brother, father, or husband first.

Men can of course also be hard to trace. If it seems your guy disappeared off the face of the earth, consider that he may have moved. Finding where his brothers or brothers-in-law lived may mean you can pick up his trail again near their location.

Take Notes as You Search

To me, looking well also entails taking notes as you search.

I know, I know. I have listed “Note it” as a separate step in my genealogy research process. But in reality, taking notes is best done in the moment that an event occurs.

Eventually, check out my post on noting your searches.

For now, I will say this:

If you wait any length of time between seeing something and jotting down what you have seen, you risk forgetting what you saw. If you are serious about getting answers to your questions, you won’t want to take that risk. So note it NOW!

Behave Well as a Researcher

Any and every time our research entails interactions with living people, looking well also implies behaving well.

I do not mean to imply that you or I ever intend to behave poorly. But I do feel that we should strive for being a little extra polite and considerate when we put on our researcher caps. Why?

1) Connecting the dots doesn’t just mean getting answers to your questions. It means making personal connections. So build a positive connection!

2) You’re more likely to get positive, helpful responses if you are positive and easy-to-help!

and 3) The general reputation of genealogy researchers can be harmed if we behave poorly when on the hunt. You don’t want to make the path more difficult for the next genealogist, do you?

Here are a few points I seek to keep in mind as a researcher:

The people we are contacting, whether they be family members, pastors of churches, county court clerks or whomever, are living busy lives too. They have more on their plates than our single request. To be quite frank, though our request comes from a burning question that we feel excited or urgent about, it’s not super likely that this is top priority for them. Be respectful of their time.

We should always show appreciation for a person’s efforts to help us. Say “thank you!”

If fulfilling your request will put a family member back financially in any way, offer to cover the cost yourself. This may mean sending a check to cover mailing costs or the classic self-addressed stamped envelope.

Even if a pastor or church secretary offers to do some research for you for free, a donation to their congregation may still be appreciated.

In the instance of government facilities like county courthouses, a donation is not necessary. Still, be someone who is easy to work with, someone who doesn’t haggle or ask for special favors like keeping the reading room open beyond posted hours, etc. (And be prepared with the appropriate tender to pay copy fees.)

Don’t ask anyone to act contrary to their organization-imposed restrictions or their personal, emotional conflicts.

Bottom line: The person you contact deserves to be treated kindly.

Look well by behaving well.

Conclusion

The ideas I have set forth in this post are really just the tip of the iceberg. Please comment if you have research tips and tricks to share or insights into research etiquette!

The next step in the research process: Analyze your finds! 🙂

[1] “1870 United States Federal Census,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/7163 : accessed 2 Aug 2021), search results for Ferdinand K* born about 1825 and living in Dodge County, Wisconsin.

[2] “1870 United States Federal Census,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/7163 : accessed 2 Aug 2021), search results for Ferdinand born about 1825 and living in Dodge County, Wisconsin.

4 thoughts on “Look Well”